It’s a new year, which means it is time for another one of these sporadic newsletter things. While I’m newer to Substack, I believe this is the twelfth newsletter I’ve written, which entitles me to a free sandwich or a meeting with some Hollywood bigwigs, where I’ll be asked to pitch a take for “Hungry Hungry Hippos” the movie.

While I don’t typically make New Year’s Resolutions, last year I did set a goal of sorts and for accountability purposes, shared it in one of these newsletters. 2024 marked the ten year anniversary of my stand up special and album, “Brooklyn,” and so I thought maybe I ought to do something to mark that… which felt both like an odd thing for me to do, but also something for me to do.

Odd because comedy is kind of an ephemeral thing. As our societal views grow and change, many jokes and premises don’t hold up so well over time. It doesn’t mean that decades old comedy can’t be appreciated years later, but it typically doesn’t hit people the way something like music does. Despite the fact it still holds up, I doubt there’s a couple at a wedding reception asking the DJ to play Richard Jeni’s joke about lobsters for their first dance.

Marking the ten year anniversary of “Brooklyn” also feels odd because it feels a bit self-indulgent. And stand up comedy in and of itself is already pretty self-indulgent. We’re people who get in front of a room full of strangers and say, “pay attention me and only me right now… and then afterwards please stop by the merch table where I’ll be selling beer koozies with my signature catchphrase, ‘Time for Cenaction.’”

At the same time, I’m a person who collects records and likes liner notes and this was an actual vinyl record and Netflix special that means something to me for a number of reasons. The first being that I wrote most of “Brooklyn” when it felt like I was being pushed out at “The Daily Show.” In my last year at the show, I was still on air as a correspondent, but off camera, I’d lost my position as a writer shortly after speaking up about some jokes that felt insensitive to me. It’s something I’ve talked about before, and while this album may not have happened without that experience, it’s not necessarily one I’m eager to rehash. My time at The Daily Show was not good, yet it’s often the first thing some people want to ask about; so if you’re one of those folks or you’re unfamiliar with the story, here’s a video from The Thread where I get into it.

Looking back, I probably should’ve gotten my union reps or a labor attorney involved, but it didn’t feel like it was worth fighting to stay somewhere I didn’t feel wanted. It sucked because that job had changed my life. It moved me to New York shortly after my car got repo’d and I’d lost my apartment in LA. With the job ending, I was questioning whether or not I should even stay in New York. A lot of the material on “Brooklyn” was me kind of working through that moment and reminding myself of the ways I’m connected to this city beyond a job.

It’s the city where I was born, where I spent summers with my grandmother watching “Sesame Street” and where I lost my father. (Not on Sesame Street) It’s also the city where, after dropping out of college to intern at “Saturday Night Live,” I thought a career in comedy might be possible. All of that found its way into the album and Netflix special and probably makes “Brooklyn” the most personal thing I’ve made.

The final reason it felt like reflecting on is that in perhaps the most cliched part of producing anything: it almost didn’t happen. When I was ready to put the special out, my record label at the time didn’t want it. It’s a shitty but understandable part of the business: they had already committed resources and promotion to other projects, so there wasn’t space or budget on their slate for this one. It’s unfortunate because a person’s work gets put in a queue and measured against which project seems more profitable versus each project being appreciated for what they are.

Because I couldn’t get out of my record deal, I figured out a loophole to make the special outside of it. My contract was to make a stand up special for TV, DVD and CD, but there was nothing preventing me from making something for streaming or a limited run vinyl album. At that time, studios weren’t really thinking about Netflix as a threat to their existence.

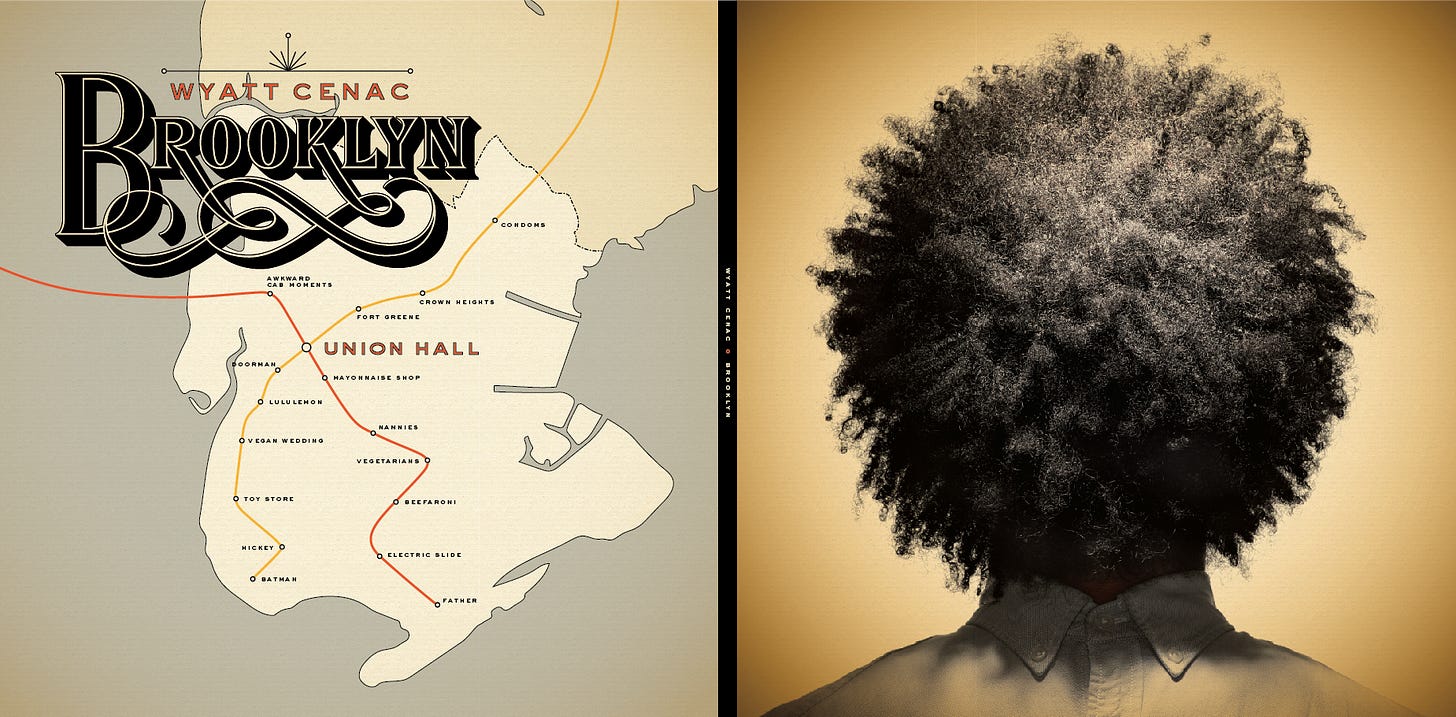

I chose to record at Union Hall in Brooklyn because it was small and intimate in a way that reminded me of where Richard Pryor recorded “Live & Smokin’.” For me, Union Hall was a venue that helped open the door for a lot of comedians and a comedy scene in Brooklyn. The shows Eugene Mirman and Julie Smith produced there cultivated more interest for stand up outside of Manhattan. My friend Michael Slaboch flew in from Chicago to record and produce the album. Kyle Makrauer shot the cover and Jessica Hische designed the album’s artwork.

A producer I worked with on “Medicine for Melancholy,” Justin Barber, suggested filming it and along with filmmakers Puloma Basu and Rob Hatch-Miller helped put together a crew and assemble a rough cut. With the Netflix special, I knew I wanted to add a second visual element, like animation or puppets, so they gave me the budget to film interstitial scenes with puppets made by James Godwin and Jean Marie Keevins. Eugene Mirman and Gbenga Akinnagbe were nice enough to make cameos.

The album and special dropped in October of 2014. It got good reviews and then got nominated for a fucking Grammy, which felt like a nice bit of validation for leaving a shitty job, releasing something despite my label’s interest and staying in New York.

Even as writing about this felt self-indulgent, ten years later, it felt worth reflecting on. Doing so, I discovered the album may be the first stand up special that premiered on Netflix to have been nominated for a Grammy. To mark the occasion, Netflix… dropped the special from their servers.

“Brooklyn” isn’t on Netflix anymore, which kind of goes back to the whole ephemeral thing. All those puppets… gone. The album is on Spotify and iTunes. But there are no DVDs of the special floating around.

As streaming has boomed, we have less physical copies of movies and TV shows floating around than we used to. Instead people now rent the privilege to see or hear what streaming companies’ algorithms decide is of value. The streamers are essentially for-profit libraries that because of their success have actually made it harder and more expensive for regular libraries to be libraries. Matt Schimkowitz of the AV Club recently wrote a piece titled, The DVD is Dead, Long Live the DVD, that eloquently lays out the moment entertainment is in right now.

Over a decade into the streaming revolution, tech companies have retrained viewers on where to find and expect entertainment. They also taught them not to expect permanence. Everything is streaming now, and we don’t mean “everything is on streaming.”

While people had grown accustomed to having VHS recordings or DVDs of their favorite movies and shows, perhaps that era was more the exception than the rule?

In the 1960’s, the BBC would often record over episodes of shows like Dr. Who and Monty Python because “broadcasters did not realise the potential value of vintage television.” Now, knowing how valuable these things can be, that might seem like an instructive lesson to make archives easily available, but there’s an old adage that people love to say and not put into practice...

Over the decades, so many shows, movies and televised moments have been lost to time. I have a friend from college, named Joi, who swears that in the 90’s she saw a sketch on “Late Night with Conan O’Brien” called “The Jep” about a Black version of Jeopardy. She thought it was hilarious and would insist it was real, but could find no proof it ever existed… so we had to have her committed.

Recently, the 25 year archive of The Daily Show was wiped from the internet. As someone who performed in a bunch of segments on that show and wrote even more that sucks. Personally, I don’t have an archive of all of the work that I did there. And if I did, licensing issues would prevent me from uploading it to YouTube.

The entertainment business is built on people saying “hey look at me,” yet I’ve watched a lot of my own work disappear. My first stand up special “Comedy Person” is no longer available to stream. It’s available to buy, but I have to split the profits with my nemesis Wyatt CERNAC.

The stand up showcase I hosted, “Night Train” featuring comedians like Roy Wood Jr., Michelle Buteau, Jon Benjamin, Janeane Garofalo, Joel Kim Booster and many other great comics is unavailable anywhere. When Discovery took over Warner Bros., an animated Steve Urkel holiday musical I wrote got dumped along with the never to be seen Batgirl movie. I worry the same could happen for Problem Areas at some point. Two other TV shows I worked on, “Fanboy & Chum Chum” and “People of Earth,” both appear to only be available for purchase. And while that’s something, it doesn’t feel like anybody will check those out when audiences have become more conditioned to pay to stream a service rather than pay to own a product.

Try to find the show “In Living Color” on streaming or to purchase. It’s not there. That show has a place in history not only for the careers it launched and how it offered representation for people of color when other sketch shows weren’t; it’s the reason the Super Bowl Half Time show exists.

The rise of streaming has put people who create television and movies into the role of becoming their own digital streaming service in an ecosystem that’s devouring content faster than viewers can savor it.

It makes me think of Marion Stokes, who spent over thirty years recording everything she could off the television because she felt it was important to preserve. The shows, the news, the ads all had value on their own and as a window into society in those times. “An activist archivist, she had been a librarian with the Free Library of Philadelphia for nearly 20 years before being fired in the early 1960s, likely for her work as a Communist party organizer.” There’s a great documentary about her called “Recorder,” which fittingly is not available to stream, but can be purchased on iTunes.

This all brings me back to wanting to mark the ten year anniversary of “Brooklyn.” Hopefully the Netflix special and some of my other projects can find their way onto my YouTube channel.

To get the ball rolling on that I reached out to a couple of friends: the cartoonist Ben Passmore, musician Donwill and animator and director Edmond Hawkins. Here’s LoFi Brooklyn.

Since there’s no Netflix special right now, this a visualizer of “Brooklyn” with some looping animation, a bunch of ten year old jokes and some LoFi beats in case anybody does want to have the first dance at their wedding include a rant about a mayonnaise shop invading Brooklyn streets.

It’s available on iTunes if you’d like to buy it, so you have something to listen to when these streaming services eventually decide to hide all the world’s content in that Batgirl vault, leaving us with nothing but Mark Zuckerberg’s acoustic rendition of “Get Low” as our only source of entertainment.

Thanks for reading. Special thanks to Leonor Mamanna and Erin Evans for being friends and sounding boards as I tried to figure out how to write about this stuff.

There’s no space for that Hungry Hungry Hippos pitch, but it was going to star The Rock as a marble fighting back against his evil hippo overlords.